An innovative solution lies in Artificial Intelligence (AI) embeddings. By translating words or phrases into a mathematical representation, these tools offer a nuanced way to perform searches that can interpret the semantic meaning and operate across different languages.

Background and Context

Machine Learning, a branch of AI, and embeddings, a crucial tool in AI, are integral to the functioning of modern search systems. Machine Learning allows these systems to learn from data and refine their operations, enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of search results. Embeddings transform high-dimensional or abstract data, like words or images, into numerical vectors. In the context of search, this process enables a more effective comparison of data points, such as documents or images, thereby refining the relevance of the search results.

The evolution of AI embeddings has been a progressive journey. Early open-source models like Word2Vec (2013) and GloVe (2014) provided an initial step, translating words into vectors based on their context within a body of text. This foundation was built upon by models such as FastText (2015), which considered smaller units of words, and transformer models like BERT (2018), which captured a more nuanced understanding of context.

Also have a look at our video to give you a quick overview about the topic of multilingual search.

The underlying idea

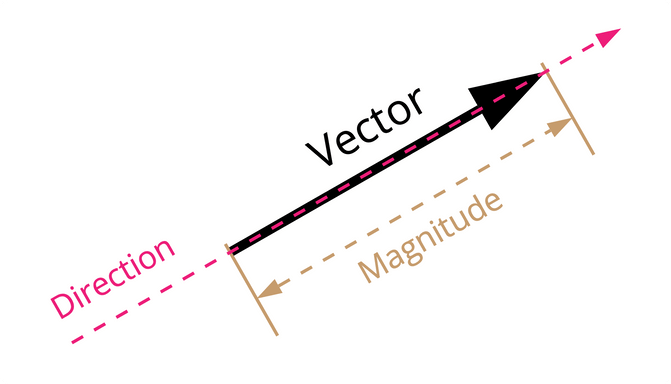

Let us now see what that looks like with a very simplified example. A vector, in basic terms, is a kind of «container» that holds numbers in a specific order. These numbers represent different characteristics or attributes of something.

Vectors can be thought of as arrows pointing in a particular direction in space, with their length or magnitude representing the quantity of what they are expressing. They help us to quantify and represent complex information in a standardised and mathematical way.

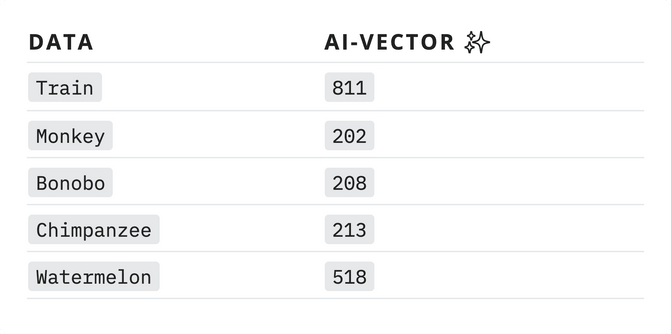

Imagine we have words we would like to index and search later in this index. Our AI-Model translates them into a vector (in our example, a single number). These numbers are not meant to be understood; they are purely mathematical and derive from an AI-Model that learned based on text, and the numbers are only meaningful inside this particular trained model.

Fig. 1 – A search index with words that got a vector from an AI-Model

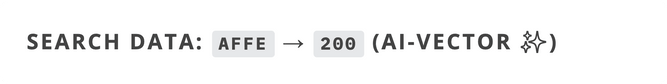

Now a user is searching for the term «Ape», and the AI-Model translates that to the number 200.

Fig. 2a – A search term that got a vector from an AI-Model

Or in German

Fig. 2b – A search term that got a vector from an AI-Model

This is where artificial intelligence is helping to translate human intentions into a numeric representation – no matter the language.

We don’t have a 200 in our Data, but we have hits that are quite close:

Fig. 3 – Search results close enough to «Ape» (Vectors ~200)

And the fruits that are not close enough are not considered:

Fig. 4 – Search results not close enough to «Ape»

In a real-world AI environment, the vector is not one number but a very complex vector with hundreds or even thousands of dimensions. This is very simplified for explanatory purposes.

Implementing a Search System with AI Embeddings

Implementing a search system with AI embeddings (vectors) involves the steps shown in our previous example. Imagine we would like to find content on a website with a vast number of pages.

The first step is to generate embeddings for the pages that will be indexed. This doesn't necessarily involve training a new machine learning model. Instead, an API (like the one from OpenAI) can be used (like Fig. 1). These APIs transform the website text into high-dimensional vectors, a bit like «fingerprints» for content. Each of these fingerprints represents the semantic content of a website, capturing its themes, topics, and context. Importantly, these vectors are language-agnostic, meaning they encode the meaning of the text rather than the specific language it's written in.

Once we have these embeddings, they are stored alongside the corresponding page in an index. This index serves as a catalogue, archiving each page's unique numerical fingerprint.

When a user inputs a search term, the system transforms this term into an embedding using the same API (like Fig 2a/b) used to generate the website embeddings. This generates a numerical representation of the user's query, also reflecting the intended search and not the literal words used.

The final step is comparing this query embedding with those stored in the index to find the closest matches (like Fig 3). The closer the vectors are, the more relevant the page content is to the user's query.

Conclusion

AI embeddings do not only match literal words, but «understand» the semantic meaning and intent behind search queries. This has made searches more inclusive, accessible, and user-friendly, empowering users to search comfortably in their native language and find relevant results, regardless of the original language of the content.

Despite the challenges of implementing AI embeddings, the technology has become widely accessible and reasonably priced, thanks to cheaply available APIs powered by advanced AI models. Furthermore, open-source alternatives are emerging that can be hosted locally, reducing reliance on other services. For countries like Switzerland, this means that search systems using AI embeddings can be hosted and managed within the country, ensuring better data sovereignty and adherence to local data protection laws.

Modern search giants such as Google have been using the power of vector search for years, signalling as well for in-page searches a shift away from traditional keyword matching towards a more context-aware, semantically rich search experience. Users are used to finding what they are looking for and not finding the right keyword that will eventually match the documents they try to find. The technology used for vector searches is also the foundation for systems not only giving search results, but also answering the underlying question. If you ask for «What are the opening hours of the tax office?» you don’t want to find the page for the opening hours, but you want to get the answer. Such AI-Driven assistance uses vector search to fetch the information they need and then answer in a concise answer. Have a look at ZüriCityGPT as an example of it.

This blog post was co-authored and edited with the help of ChatGPT and Janina Kürsteiner. As a free software advocate at Liip, I'm aware of the ethical and licence implications we will face in the future with AI. This text is licensed as creative commons (CC BY-SA 2.0).